In the blog series "A view of Waste from ..." we look beyond the borders of the Netherlands and Belgium. Because how do other cities and countries deal with their waste streams? What can we learn from them- and what not? In this blog, Aniek Schaeffer- junior Waste Engineer at Milgro- zooms in on London.

The English capital- characterized by red telephone booths and Big Ben- has big ambitions: by 2026, no more biodegradable or recyclable waste should go to landfills. In addition, 65% of municipal waste must be recycled by 2030. The ultimate goal? A Zero Waste city.

The streetscape

With 9.84 million residents and 20.3 million international visitors annually, one thing immediately stands out on London's busy streets: the conspicuous lack of public waste receptacles. It can take minutes before a trash can comes into view. The bins that do exist usually have two compartments: one for residual waste and one for a mix of recyclables such as paper, cardboard, aluminum and plastic. Separate collection of multiple streams - as is common in the Netherlands - hardly happens here.

Yet recyclable waste in London is often well separated from residual waste. This is partly because many packages clearly state whether the material is recyclable and because instructions are often present at waste bins. There is also a strong incentive to dispose of waste neatly: those who leave waste on the street risk a fine of between £400 and £1,000.

Household waste

Waste discarded in the city by tourists or residents usually ends up neatly in the designated bins- as described above. However, household waste in densely built-up neighborhoods is a different story. Residents often put it on the street in loose bags and boxes. These are regularly torn open by gulls or foxes in the moring, resulting in messy streets. In more spacious suburbs and near larger flats, things are neater: there, roll-off containers are used, which makes for cleaner streets.

Creative and innovative collection methods

London's zero waste ambition is also reflected in creative and innovative collection tools and communications. For example, small mirrors can be found on the streets with the text, "Mirror mirror on the wall, litter left here reflects badly on us all." Along the Thames float pontoons that remove litter from the water. At some to-go stores, cups can be separated into lid, cup and liquid, so that the materials are directly collected separately.

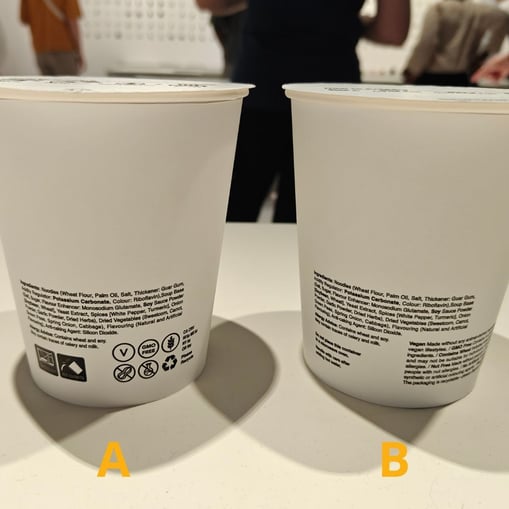

Japan House London featured an exhibition on the use and design of icons. The exhibition featured two packages: one with clear symbols (A) and one with only very small text (B). The difference was significant: icons offer clarity at a glance, while text takes time and effort to read.

London's waste policy matches the design of public bins: in a busy city with little space, it is simply difficult to place many different containers. Whereas in Rotterdam and Amsterdam household waste is often collected in one bin and later sorted by machine, London takes an approach that involves the user directly by having them look at the recycling symbols on the packaging.

London: the Zero Waste capital of England

London is already taking visible steps toward its zero waste goals, but there are still clear challenges. Creative campaigns, clear instructions and smart collection solutions show that awareness and behavioral change are on the streets. At the same time, achieving sufficiently structured and closed collection methods remains a major challenge in a densely populated city.

Ambitions for 2026 and 2030 are high. To achieve them, London will not only have to continue to innovate, but also make practical improvements that make separating and collecting waste easier and cleaner for everyone.

Read also

A view of waste from New York

Stay informed

Want to stay up to date on all new developments? Follow us onLinkedIn, or subscribe to the newsletter. Are you curious about what Milgro can do for your business and waste process? Then get in touch.